The City of the Future Looks Like a Former Military Bunker in Taipei

Back in 2016, I wrote an article for How We Get To Next on an informal settlement called Treasure Hill, in Taiwan, that could be a prototype for the future of sustainable urban living. How We Get To Next is still online in archived format, but with bitrot being what it is, I'm also reproducing this story here on my blog.

On the south side of Taipei, nestled in the hills behind the Gongguan Metro Station, is a community with a rather unusual history. Once a military outpost, it’s now a cluster of gray concrete, red brick, and sheet metal stacked haphazardly, rising some 260 feet (80 meters) above the surrounding city. Steep staircases lead to twisting alleyways filled with graffiti and confusing sculptures. In one courtyard, tourists can often be seen sitting on a pair of giant fortune cookies.

This is Treasure Hill–a prototype for what one architect believes is the future of sustainable urban living.

The district began life almost a hundred years ago as an anti-aircraft position built by the occupying Japanese army. After the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II, it passed into the hands of the Kuomintang government of China, which maintained it during the Chinese Civil War against the threat of Communist air attacks from the mainland.

But those attacks never came, and the soldiers manning the position began to get bored. Some found local wives and had children, beginning to complain that the bunkers below the guns weren’t a pleasant environment to raise a family.

Over time, the bunkers became the foundations and cellars for a small group of houses, which expanded farther when the government decided the site had lost its strategic value and moved the anti-aircraft guns elsewhere.

The soldiers were ordered to move with the guns, but many refused–they wanted to stay with their families. Other war veterans who fled from mainland China joined the community, too. Meanwhile, the city of Taipei grew around the hill. The newly unemployed soldiers began farming the nearby land, as well as harvesting waste from the city to turn it into materials and energy.

For decades this status quo held, even as friction grew between the city government and the residents of Treasure Hill. Officials saw it as a slum–its improvised buildings, built up over the years amid piles of trash, were not only unsightly, but also in flagrant violation of the city’s safety codes. In 2002, the whole settlement was declared illegal and the authorities began the process of clearing the area and turning it into a park.

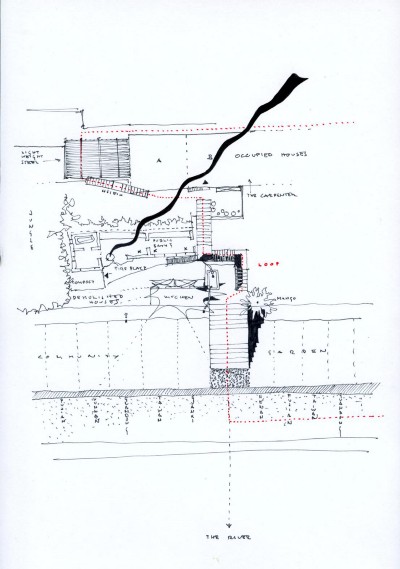

First the city tried to bulldoze the homes around the edges, but the residents just retreated to the buildings on top of the hill and the decaying bunkers within, refusing to leave. The authorities then attempted to disrupt the community by destroying the bridges and staircases that connected the different parts of the settlement.

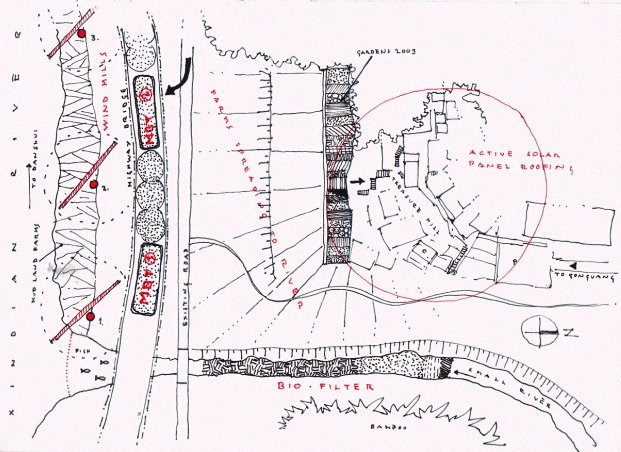

That’s when Marco Casagrande, a Finnish architect, stepped in. The Taipei City Government had asked him to study the “organic layer” of the city and how they could react to it by means of urban planning. “I found out that Treasure Hill was actually much more ecological than the modern city,” he said. “They were recycling all their organic waste. They were even filtering water to be reused.”

He persuaded the city to halt the bulldozers and recruited 200 volunteers from the local community to help him rebuild. “We worked together and we remade the farms, rebuilt the connections between houses, and so on,” he said. “Then rumors started to spread across the city. The media started to follow us, and when the media came, the politicians were next in the ecosystem–the same people who were destroying it three weeks earlier.”

Unfortunately, there was still a problem–the city couldn’t overlook the building codes. But Casagrande found a loophole: He declared that since the houses had been handmade, they were a form of art. “The city commissioned me to make a public artwork, and Treasure Hill is the artwork. That’s where [people] live now,” he said. “That’s how they rationalized it.”

In 2010, the city took the project a step further–rebranding Treasure Hill as Taipei Artist Village, alongside several other sites around the city. Today, artists from around the world can apply for the Treasure Hill Artist-in-Residence program, while walking tours are available to guide visitors around its twisting streets and alleyways.

“The politicians were next–the same people who were destroying it three weeks earlier.”

But Casagrande believes it can still be much more. “Treasure Hill surfaces many of the future possibilities of environmentally sustainable urban living,” he wrote in 2006 in Taiwan Architect magazine. “When the old farming-based values of Treasure Hill and those of the surrounding modern city meet, a new kind of ecological urbanism might be born.”

“I don’t mean taking steps back technologically. On the contrary, I suggest reinforcing the existing urban farming qualities of the Treasure Hill with state-of-the-art environmental technology solutions and so see the Treasure Hill settlement as a living laboratory of sustainable urbanism. These new technologies and solutions must respect the way of life of the Treasure Hill veterans–the active solar panels and mechanical biological treatment units of organic waste must make room for the grandmothers.

“The Taipei City Government should see the possibilities in Treasure Hill and react to them. The grandmothers and urban farming must stay but new environmental technologies must also be tested in a way that can later be multiplied in Taipei and in the rest of the Taiwanese cities. The solutions must be site-specific but suitable environmental technology solutions already exist. It is only a question of will to combine these two.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019.