Tenday Notes 11 May - 20 May

Every ten days I share a quick digest of what I've been working on. Here's the latest. You can find more in the series here.

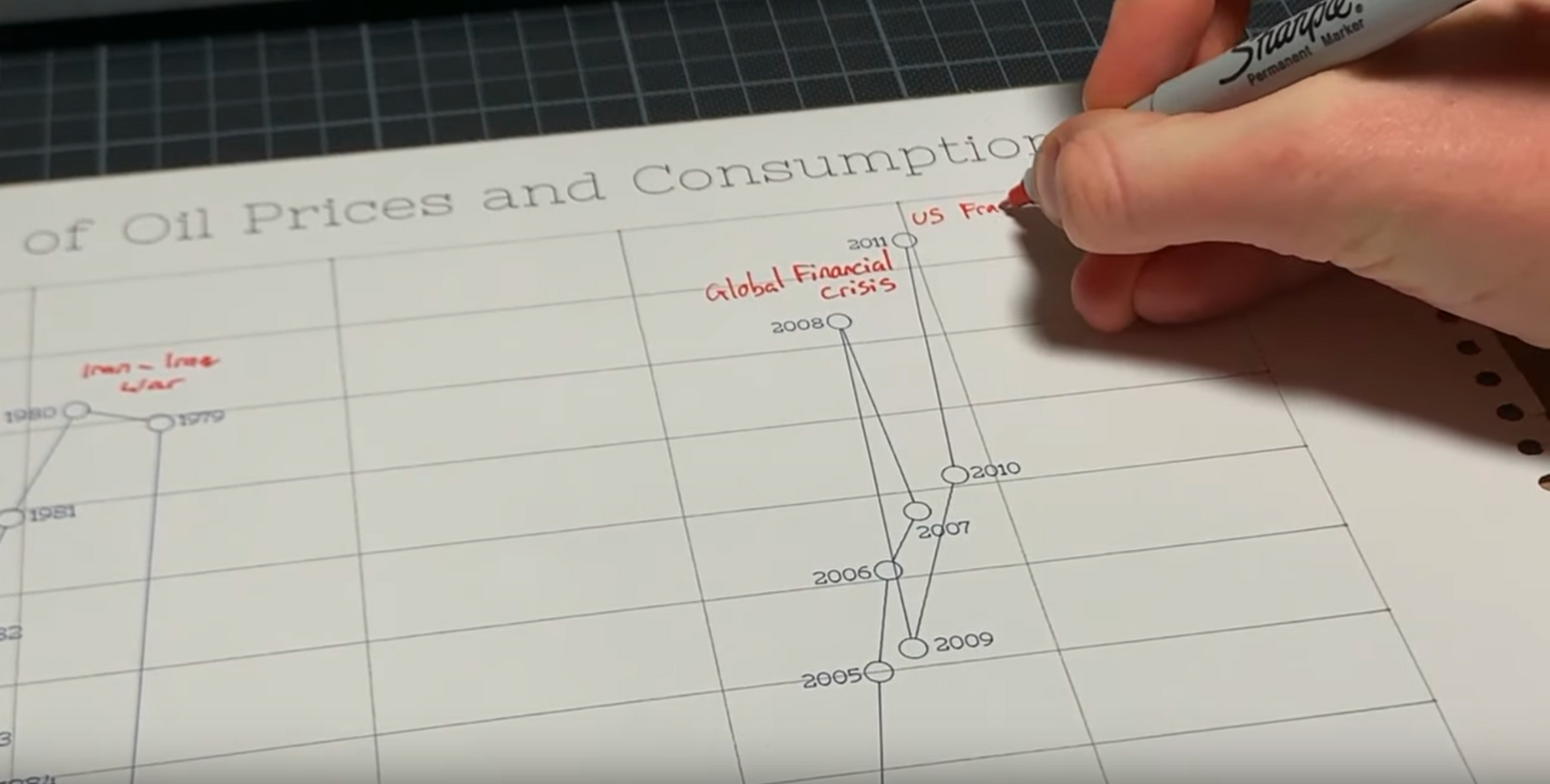

My first Dataplotter video is done! It's a history of oil markets and production, in the wake of the recent crash in oil prices. You'll see that such a crash isn't necessarily unprecedented, but things may be different this time.

I made it with my pen plotter, which is super-satisfying to watch. You can find it over on my Plottervision YouTube channel.

Now it's out there, I've been surprised by how lovely the response has been to this one. It seems to have hit a chord with people. Now I've just got to come up with a new concept and do it all over again!

I've written up a few notes about the somewhat tortuous production process on my blog, for those who are curious. Doing things the first time is always a pain! Things I already want to fix for the next one are video quality, swapping the music for (or just adding?) plotter noise, and a less complex plot (this was a bit of a nightmare to edit).

I've also written up an article for Nightingale on why pen plotters are such a great tool for data visualisation. Here's an excerpt:

One of my favourite things about the plotter is that it sits right on the boundary of the physical and the digital. You’re using pens and paper, but they’re controlled with digital precision. Want a big chunky pink marker? You got it. Want a fine, smooth black line? Also cool. Want to write in sparkly gold ink on black paper? Not a problem. That fact alone immediately elevates the plotter over a printer for me.

A lot of people have been asking me what life is like in Sweden at the moment. It's hard to say what it's like in Stockholm, where I understand things are different, but the situation in Gothenburg is well-represented by this short essay published in National Geographic.

Some of the exposition (the author listing the precautions she took in visiting each location) is a little tedious, but the conclusions are sound. In short, richer people are mostly carrying on as normal while poorer people (who are less likely to be of Swedish origin) are more worried. The crux is this bit from near the end:

If you ask Swedish people, they’ll insist that they’re social distancing. In downtown Gothenburg, the hub of our city’s social scene, what that really means is that people are hanging out but not hugging each other.

Worth a read, and has lots of nice photos of the city too.

I also loved the intro of the latest Dense Discovery (one of the few tech/design newsletters I like). It talks about how all our TV shows and movies depict awful humans being awful to each other, and quotes historian Rutger Bregman* talking about why:

If you ask the question ‘Who benefits from this cynical view of human nature?’, the answer is quite simple: it is those in power. Because if we cannot trust each other, then we need them, then we need the generals and the monarchs and the kings to keep us in check. It’s an argument for hierarchy. And this is why the argument I make in my book – that people are actually pretty decent – is a really dangerous idea. If you really think it through, it means revolution. It means we can organise a society in a completely different way. And it’s also the reason why throughout history, those who have advocated a more hopeful view of human nature have often been persecuted.

I've long been frustrated by this. I have a personal rule that I just don't watch shows or movies (or read articles) where the story is just awful humans being awful to each other. It's not relaxing. I feel awful afterwards. It makes me less social and less trusting. It's not how I like to spend my free time.

Which is to say that I would love to hear your recommendations of TV shows and movies where the protagonists are people doing good things. Schitt's Creek, Steven Universe, Parks & Rec fall in that category for me, but they're so few and far between. Please - send me your suggestions.

- Bregman has a new book out, which looks pretty interesting.

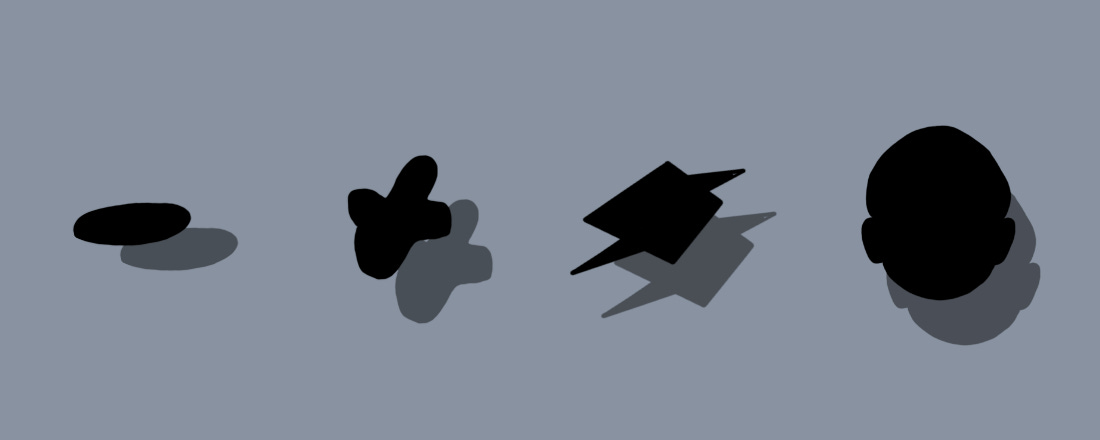

I loved being a part of the Data Visualization Society's latest "fireside chat" - on sketching. I do quite a lot of sketching, both when I have something to visualise and when I don't, and it was really nice to get the chance to unpack some of that process and figure out why I do things the way I do. If you missed the session you can catch it here.

I've written up some of the advice I gave and summarised it in a blog post (a recording of the session is in there too). The key benefit that sketching has brought me is a way to break logjams of thinking - when I get stuck on the computer, I start sketching. When I'm stuck sketching, I return to the computer. Have two different ways to tackle a problem dramatically increases the chance that I can deal with it.

If you're doing data visualization work and you're not sketching, then I recommend starting immediately with the closest pen and paper you can find. Pick a theme. Draw some obvious shapes. Then your brain will automatically start drawing some less-obvious shapes, until you've got something really new and interested to get excited about. That's the magic.

The pen plotter YouTube channel is growing. The success of Dataplotter gained us a nice bunch of subscribers, and I'm hoping that consistent plot posting is going to keep it growing.

The only part where I'm not really meeting the original plan is in educational content. It's relatively easy to film the plotter doing its thing, but a bit more work to make a tutorial video. On the one hand, I don't feel like I'm quite at the point where I know enough to start teaching others. But on the other hand, I know that teaching is the best way to learn. Probably one of those situations where I just need to bite the bullet, jot down a quick summary about what I want to say on a subject, and then start.

If any of you have made educational video content (esp for YouTube) then I'd love to hear tips, dos/dont's, and any other things you've learnt along the way.

There's a nice bit in Thom Wong's 100% newsletter on what he calls "passive income for the soul". That's his name for the practice of doing a thing you like repeatedly without a specific goal. That might be cooking, writing, photography, coding, exercise or more.

The goal is to increase your mental wellbeing as passively as possible, so that when you need a bit of resilience on a particularly bad day, you've got some stored up. He writes:

Keeping your soul satisfied can’t be your full-time job. It can’t be something you have to work at all the time. Because then you’d be emptying out the vault as fast as you fill it up. Soul-based passive income is when something you do requires little to no effort but delivers a lot of satisfaction.

This is, of course, a silly 2020 name for something that people have been doing forever. But that doesn't make it less good advice.

My soul-based passive income streams, right now, are mostly my plotter experiments - which involve aspects of code, design, art and research. A few people have asked if I'm planning to monetise the YouTube channel, or sell prints, or something else. Honestly, I've got no idea. All I'm trying to do is make a lot of things so that I get better at it, and fill up my mental wellbeing in the process. It works rather well.

There's a bit of a chain of causation to set this one up, so bear with me. I was listening to a fantastic interview with economist Tim Harford on the Conversations with Tyler podcast, and he mentioned a question that Brian Eno had once asked him. Here's the question:

“If you were transported back in time to the year 700, what piece of technology would you take — or knowledge or whatever — what would you take with you from the present day that would lead people to think that you were useful, but would also not cause you to be burned as a witch?”

Tim's answer was the Langstroth Beehive, which I was not previously aware of the existence of, and my life now feels richer as a result.

But the beehive isn't the the point of this story. I was talking to Silfa about this idea of things seeming like witchcraft, and off the back of the famous Arthur C Clarke quote about any sufficiently advanced technology being indistinguishable from magic, I came to a realisation that perhaps part of why people like watching pen plotters do their thing is because they're insufficiently advanced. They're distinguishable from magic.

Let me explain. Most technology today, to most people, is essentially magic. Many people don't know how a speaker operates, or a camera. They definitely don't know how a laptop or mobile phone display works. Happily no-one gets burned at the stake as a result any more, but at some point over the last century or so we passed the point at which most technology is understandable to most people.

A plotter is different - it's fairly easy to see how it works. There are three motors - one handles horizontal movement relative to the page, another handles vertical movement, and the third controls whether the pen is on the page or lifted above it. There's the small matter of how it converts magical computer files into motor movement, but the moving parts, at least, are pretty understandable. It helps that they're largely on show, too.

And yet, the things that this perfectly understandable machine produces still seem magical. We're unused to seeing pens draw perfect curves, evenly spaced. We're unused to seeing seemingly hand-drawn shapes lined up on paper in nice grids.

I wonder sometimes if I write too much here about plotters, but I'm increasingly fascinated by their weird combination of the physical and the digital, and how that affects people when they see it. It feels like a very rich seam of interesting discoveries to mine.